By Sybil Lewis

Despite India’s robust government immunization program—which provides 11 different vaccinations free of cost—immunization rates remain low, particularly among poor populations. According to a 2015 University of Michigan study, only 57 percent of children younger than three in India are fully vaccinated. A nationwide survey conducted by UNICEF in 2009 found that many children are not fully immunized because their mothers and caretakers did not understand the vaccines, did not know where to get them, did not feel they were needed, or found vaccines shortages at health clinics.

Despite India’s robust government immunization program—which provides 11 different vaccinations free of cost—immunization rates remain low, particularly among poor populations. According to a 2015 University of Michigan study, only 57 percent of children younger than three in India are fully vaccinated. A nationwide survey conducted by UNICEF in 2009 found that many children are not fully immunized because their mothers and caretakers did not understand the vaccines, did not know where to get them, did not feel they were needed, or found vaccines shortages at health clinics.

With this in mind, three UC Berkeley MBA students— Anandamoy Sen, Erik Krogh-Jespersen, and Sanat Kamal Bahl—and Julia Walsh, a Cal professor of maternal and child health and international health, began in 2012 to rethink potential solutions. The team decided that the Indian vaccine deficit was due not to lack of supply, but to an information problem—and could best be addressed through a cellular vaccination tracking technology, which they called Emmunify.

“When we looked at household surveys in Uttar Pradesh that asked why children were not getting vaccinated, we found the major problems were the families didn’t know the importance of them, didn’t know when they were supposed to go, and when they did go there were tremendously long wait times and possibly no vaccines,” said Professor Walsh, co-founder of Emmunify. “So when a mother does a mental cost-benefit analysis of waiting to get the vaccination or working for a day, she does not see the benefit of the vaccine.”

“When we looked at household surveys in Uttar Pradesh that asked why children were not getting vaccinated, we found the major problems were the families didn’t know the importance of them, didn’t know when they were supposed to go, and when they did go there were tremendously long wait times and possibly no vaccines,” said Professor Walsh, co-founder of Emmunify. “So when a mother does a mental cost-benefit analysis of waiting to get the vaccination or working for a day, she does not see the benefit of the vaccine.”

Another challenge to universal immunization is the paper record keeping system in India; records are often easily misplaced, resulting in missed or duplicated vaccinations. The most recent National Family Health Survey in India found that only 38 percent of mothers were able to show their child’s vaccination card.

To address these challenges, Emmunify plans to provide a portable electronic medical record that digitizes and stores immunization records, replacing cumbersome paper records. It also plans to send SMS reminders to families about when their next vaccinations are due and where they are available.

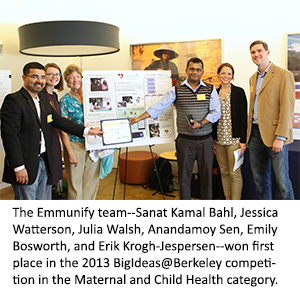

Emmunify got its start through the UC Berkeley’s 2012 Hacking Health competition, which awarded Sen, Krogh-Jespersen, and Bahl the grand prize of $2,000 to build a prototype. With Walsh as their faculty adviser, the team then won first place in the 2013 Big Ideas@Berkeley competition in the maternal and child health category and used the $8,000 award money to send two team members to the New Delhi slums in July 2013 to test Emmunify’s usability and feasibility. By partnering with Aarushi Charitable Trust, an organization of community health workers in the New Delhi slums, Emmunify was able to conduct stakeholder interviews with health workers and focus groups with mothers.

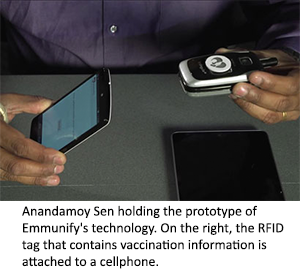

The Emmunify team aims to implement a multi-step process. First, a village health worker would use a portable, battery-powered tablet with Emmunify’s software to register a family’s health information and assign each family an ID number, which is programmed onto a portable chip (RFID tag) placed on the family’s phone. Once the family is registered, it will receive SMS or voicemail reminders about upcoming child vaccinations. When the family arrives at the clinic, its RFID tag will be scanned to confirm and update immunization records, preventing duplication. The final step is to store the health information from the tablet onto the Cloud, where an application will generate and send future automated messages.

The Emmunify team aims to implement a multi-step process. First, a village health worker would use a portable, battery-powered tablet with Emmunify’s software to register a family’s health information and assign each family an ID number, which is programmed onto a portable chip (RFID tag) placed on the family’s phone. Once the family is registered, it will receive SMS or voicemail reminders about upcoming child vaccinations. When the family arrives at the clinic, its RFID tag will be scanned to confirm and update immunization records, preventing duplication. The final step is to store the health information from the tablet onto the Cloud, where an application will generate and send future automated messages.

Anandamoy Sen, Emmunify’s co-founder and mobile technology professional, said the organization’s main innovation is its adaptability to India’s rural health context. He noted there have been other prototypes of electronic record vaccination systems, but they require a Wi-Fi connection, which is scarce in rural villages, and use bulkier hardware that is easily damaged. What sets Emmunify apart, he said, is its offline design. An Internet connection is used only to send information to the Cloud; during the registration and vaccination process, no Internet, phone service, or electricity is required.

Much of what Emmunify aims to do is enabled by India’s robust mobile phone market. According to a 2010 UN report, for every 100 people there are approximately 45 cell phones. Emmunify can rely on SMS reminders because the RFID tag placed on families’ phones is designed to operate on any type of mobile.

Emmunify may be attractive to health care providers due to its simplicity and cost effectiveness.

“Paper [vaccination] cards are estimated to cost about a US$1.25 per child, whereas the tag is inexpensive, costing US$0.25-0.50 each,” said Professor Walsh. “We also can buy consoles and tablets for the health workers at less than US$100 each.”

Walsh noted that developing the necessary software and cloud analytics is the most challenging and costly aspect of Emmunify’s technology. The software—the tablet-chip interface, the tablet-cloud interface and cloud analytics, and the automated family reminders—will be interconnected. To date, the team has completed the RFID tag and has progressed with the user-interface for the health workers console. But they are still working on the Cloud-console software and analytics.

The potential impact of a technology like Emmunify extends beyond the health benefits of vaccinations. “If you are fully vaccinated, you will be better nourished, do better in school, stay in school longer, and have the chance to get out of poverty,” Walsh said. “We estimate that in places like the New Delhi slums and the poor populations of Uttar Pradesh or Bihar, if you vaccinate an additional hundred kids, you save two lives.”

In the long run, Sen said health information stored in the Cloud could help health clinics forecast supply and demand for vaccinations, preventing shortages that have deterred mothers from getting their children vaccinated.

The Emmunify team has always known that cooperation with and buy-in from the Indian government is essential. The government plays a large role in the administration of vaccinations through its Universal Immunization Programme, which since 1978 has provided vaccinations of preventable, yet life-threatening, conditions to children free of charge.

In October 2010, the Indian government implemented a voluntary Universal ID program (UID), which stores citizens’ biometric data and assigns them a unique identity number, with the goal of improving and reducing corruption in the distribution of public services. Emmunify does not plan to integrate with the UID program because, said Sen, many rural clinics do not have the scanning technology to obtain biometric UID data and the UID program does not include the vaccination reminder software. However, Emmunify may use the national ID as a verification method for families’ RFID tags.

Next steps for Emmunify include registering as a nonprofit and pilot testing. Emmunify recently won third place in the 2015 BigIdeas @ Berkeley Scaling Up competition, receiving a $5,000 award that will help the team test all of Emmunify’s technology—from the chip to the SMS reminders—with families in the New Delhi slums in early 2016.

Emmunify’s technology may not be limited to India. Walsh said Emmunify is working closely with DHIS 2, an open source information system functional in 30 countries, including eight Indian states. Once the pilot test is complete, Emmunify plans to adapt its software to be compatible with DHIS, allowing for the possibility of expansion into other countries.

When the Big Ideas student innovation contest launched 10 years ago, it was a novel concept: give teams of students with potential breakthrough ideas small sums of money and a variety of supports and see what happens. Over the past decade, a lot has happened.

When the Big Ideas student innovation contest launched 10 years ago, it was a novel concept: give teams of students with potential breakthrough ideas small sums of money and a variety of supports and see what happens. Over the past decade, a lot has happened.